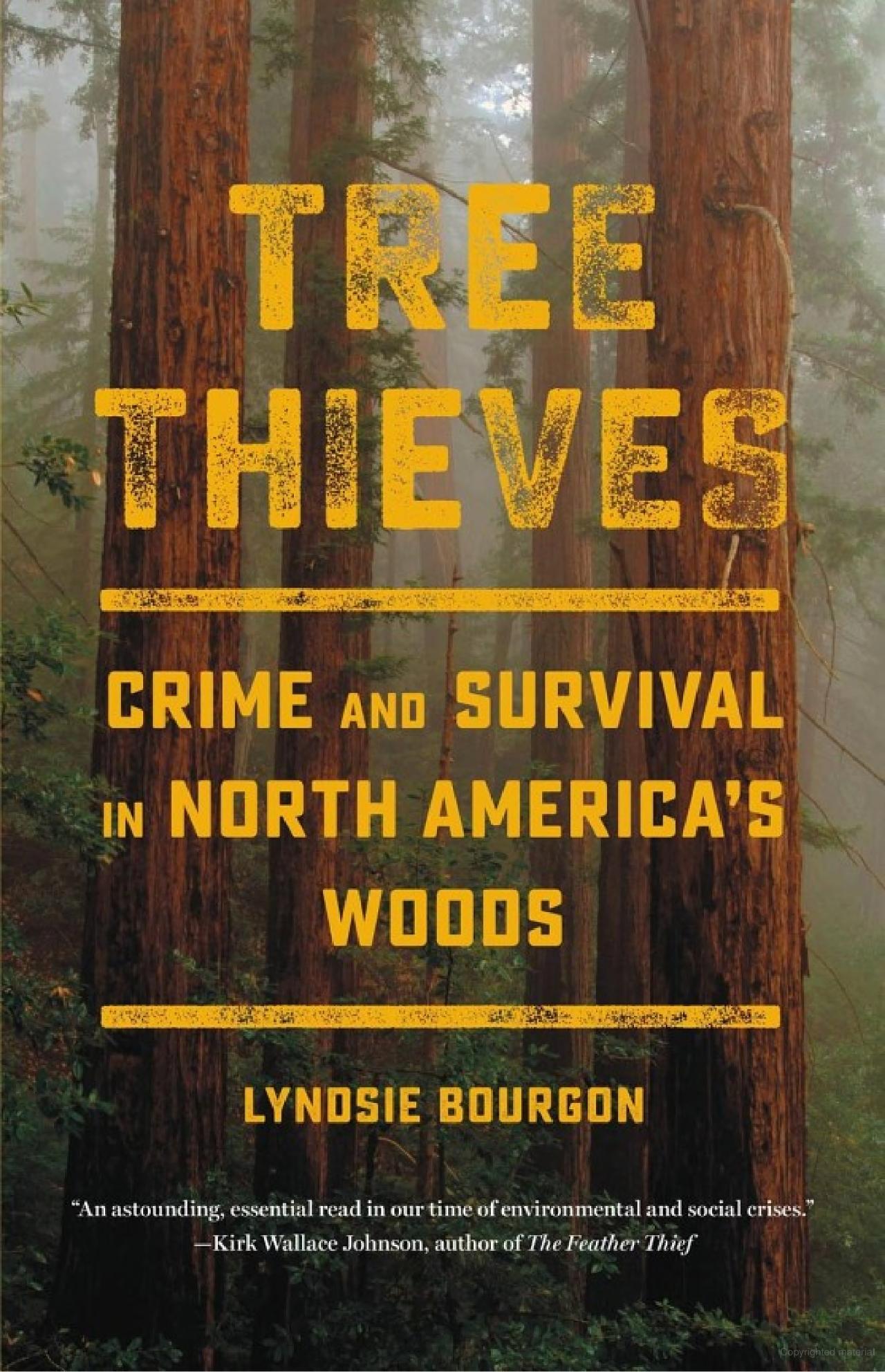

On Lyndsie Bourgon’s “Tree Thieves”

Part of Bourgon’s book explores a seemingly familiar story about poverty and bureaucratic corruption in Amazonia, where bad squatters needing room shift into stands of trees they really don’t personal. Logging ensues, and so do illegal mining and oil drilling. Considering the fact that the space is too big for the minimal amount of rangers to address, the authorities make use of strategies like sound-sensitive GPS devices, hidden in the trees higher than the stage exactly where an illicit chainsaw may well function. When the sound of a saw is relayed to a law enforcement camp, the rangers are occasionally able to respond and make arrests. Yet, in brazen bunches and in single, stealthy cuts, Infierno is slowly but surely becoming denuded of its tallest and most worthwhile trees, these types of as the graceful ironwood, a person of Bourgon’s favorite species.

She estimates that as significantly as 80 p.c of harvested wood in Amazonia is removed illegally. These losses chip away at the 120 million metric tons of carbon saved in the unlogged forests there. As far as Bourgon is involved, international timber firms in Peru qualify as “tree thieves” just as substantially as the very poor squatter households.

Despite the fact that powerful, Bourgon’s chapters on the Amazon are placed at the back of the ebook, just about like appendices. Evidently, this is for the reason that her most powerful reporting, conducted soon after her return from South The united states, will take position in the Pacific Northwest, close to in which she lives. The temperate forests of North The united states are also plagued by tree robbers, with an estimated $1 billion really worth of trees illegally slash every yr.

The true interest of Bourgon’s e-book is the coastal redwood zone among Northern California and Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Right here the eponymous redwoods, blended with cedar, maple, and Douglas fir, suck moisture from ocean fog and hefty rainfall and purchase incredible girths. In its all-natural state, a redwood forest is extraordinarily dense. “[J]ust two acres of this land can host virtually 10,000 cubic meters of biomass,” Bourgon notes, and gigantic root devices “continue to feed the forest long just after the entire body of the tree has disappeared.” Fairly miraculously, a redwood is ready to regenerate by itself by sending up a spate of new trees from a one downed log. Soggy problems don’t bother redwoods due to the fact their wood is just about rotproof. As community gardeners know properly, redwood chips make a great mulch but a awful soil amendment, and redwood back garden furnishings seemingly lasts permanently simply because of the resistance of the wooden to breaking down.

The redwood’s resilience is, having said that, its Achilles heel — the reason for 150 several years of overcutting. Involving 1850 and 1990, claims Bourgon, some 96 per cent of the authentic stands have been shed. The surviving trees are confined to a 35-mile-large belt in close proximity to Highway 101 in California. Bourgon focuses on the threats to these several remaining large trees, a single just one of which can generate hundreds of pounds. Sticking out like sore thumbs in condition and federal parks and abutting lands, the giants are straightforward targets for poachers. Bourgon’s major goal — in depth at close variety in her textual content — is to examine the exploits of the tiny-scale cutting and poaching having position in this redwood idea of Northern California, with lesser emphasis on the destruction of previous-expansion rainforest in her residence region of British Columbia.

Although acknowledging that stealing an old-growth redwood or cedar is improper, even an abomination, Bourgon wishes the reader to consider “survival” — the phrase is yoked to “crime” in her subtitle — as the motive for illicit action. Just as we could sympathize with the faceless peasantry in the Brazilian Amazon, carrying out what they have to do to endure, we could come to do the very same with Bourgon’s American redwood burglars. On the one hand, they are a motley forged of informants scarcely bothering to disguise their illegal techniques, but on the other hand, when depicted in their financial and historic context, they turn out to be more durable to choose. These people are happy and self-reliant individualists, quintessentially American in some respects. Some audience may well grudgingly appear to admire them.

Coming into their world, the initial detail we discover is that a poacher eschews the term “poaching.” His enterprise is to “take” solitary trees when law enforcement is hunting the other way, especially if the possession of the redwood is in question. Historian Bourgon evokes Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham, who skirmished around the “taking” of forest solutions like sport and wooden from what have been ostensibly public lands. “[T]rees have been an integral component of the commoner’s daily life,” she writes, “and the forest was dubbed ‘the poor’s overcoat.’” By the 17th century, wood-gathering for housing and heating grew to become a crime in Europe and North The us as personal holdings were being prolonged and parks established. The forests turned “a spot of folks criminal offense.” The poorer family members who relied on the forest for sustenance objected to currently being relegated to the incorrect aspect of the law — a theme Bourgon often returns to, citing “social resentment” and “economic inequality.”

The California coastal city of Orick is Bourgon’s base camp. Its very first sawmill began operating in 1908. By the 1950s, when very clear-chopping grew to become the dominant practice, logging was no more time a compact-bore action. Poaching was not an issue originally due to the fact there was lots of do the job and a good earnings in the mills. But when winter season storms swept by way of, most destructively in 1955 and once again in 1964, the clear-minimize slopes turned into muddy hellscapes. In the ’64 storm’s aftermath a ranger explained “a lunar landscape, with the uncooked edges of the mountains exposed.” Therefore the obvious have to have for environmental regulation, whose successes would finally travel the massive sawmills out of company.

Help you save the Redwoods League and the Sierra Club lobbied to lock up the big trees Redwood Nationwide Park was selected in 1968. A generation later on, the northern noticed owl, which involves old-advancement forest, acquired endangered species defense, placing much more of the woods out of the chainsaws’ achieve. Sawmills in Asia commenced to contend with American mills to approach raw timber. It all arrived to a head in the 1990s, the bitter period of time acknowledged as the Timber Wars, as ardent environmentalists confronted truculent woodsmen. By the transform of the century, the power of the lumber businesses experienced collapsed, and the most insular of the logging people, buckling beneath the loss of their livelihood, succumbed to divorce and drug abuse. Bourgon describes the upshot: the emergence of disaffected outlaws who turned their capabilities to poaching.

Most redwood poaching is selective almost never is the total tree taken. Like an oyster, a mature redwood harbors a variety of pearl acknowledged as a burl. Increasing at the foundation of the tree or swelling just underground, the knob of a burl consists of thousands of kilos of smooth wooden unblemished by knots. Just as a rhino may perhaps be killed only for its horn, a redwood might be destroyed for its burl. If the tree is gutted but left standing, it might not be killed outright, but its wounds may well doom it to insect infestations. At the flip of the 20th century, poachers began supplying local furniture makers with high quality burl wooden. The paperwork certifying a burl’s provenance was perforce fishy. Fly-by-night burl shops started to pop up on the outskirts of the condition and nationwide parks.

Bourgon’s tree robbers preserve that they’re only seeking to make a dwelling like absolutely everyone else. She managed to acquire the self confidence of a half dozen who talked to her on the report, which includes Danny Garcia, Derek Hughes, and Chris Guffie. They acknowledged not only redwood poaching but also unlawful drug use, the 1 routine feeding the other. Garcia, a methamphetamine person, was a expert in harvesting redwood burls and promoting to outlets that ring the forest. He was jailed briefly in 2014. Derek Hughes acted additional like a craftsman, utilizing a lathe to “turn” wooden and make bowls and vases for sale. Instead than steal wood in the forest, he foraged for redwood logs that had washed up on public seashores. (Harvesting such driftwood is unlawful.) We look at Hughes conquer a number of criminal expenses, but he faces a reckoning in court docket by the stop of the guide. And Chris Guffie had the reputation of “the most prominent outlaw” in Orick. He overtly bragged about robbing wood from the parks and was said to use wigs and sunglasses to foil the authorities’ hidden cameras. Guffie was deemed way too clever to nab, that’s why the officials’ concentrate on Garcia and Hughes.

Numerous lesser thieves, and a mix of wives and girlfriends, fill out Bourgon’s checkered solid. In the meantime, the legislation enforcement figures in her story acknowledge to Bourgon that they’re overmatched. As in the Infierno tract in South The usa, redwood thieves usually function at evening, and have to be caught in the act if rates are likely to stick. Bourgon information the rangers’ irritation. The seem of the criminal offense, Bourgon writes, was “the choppy fluttering of a one chain saw whirring to life in the deep woods.” When she appears more than the border from California to Canada, she finds significantly the same frustrations. Less than 10 {3ad958c56c0e590d654b93674c26d25962f6afed4cc4b42be9279a39dd5a6531} of forest crimes documented there are processed in courtroom.

Bourgon is not with out remedies. As at recreation parks in Africa, Bourgon indicates that “community forests” be established in redwood nation. Instead than parks patrolled by armed guards, area guardians could be hired to act as the eyes and ears of the forest. Poachers may be turned toward honest perform. As it now stands, the harder the rangers behave, pulling around suspects on the highway and issuing threats, the additional the poachers dig in. Paranoia flares. “They don’t want me to be their enemy,” just one man warns the author. “They won’t have any trees remaining.”

Tree Thieves is a vividly composed, good piece of investigative reporting. But does Bourgon conclusion up admiring her topics a minor bit also a lot? In her acknowledgments area, she praises the “deep honesty” of Garcia and the other people, crediting them for answering “very individual inquiries.” “Commitment” and “kindness” are between their superior traits. Truly? A lot of years ago, I wrote a similar review of deer jacking in Massachusetts — the out-of-season taking pictures of white-tailed deer. The chief of the outlaw gang took me into his self esteem. His thoughts about jacking deer had been complicated. On the just one hand, he felt entitled, as a male with neighborhood roots, to harvest venison to feed his loved ones. On the other hand, he cultivated a type of anger about the deer’s Bambi graphic, the oohing and aahing about the really deer by character lovers who invested their weekends in the nation. The two thoughts merged to justify his unlawful action.

Bourgon’s poachers furthermore deploy a raft of arguments to justify what they do. They egg just about every other on when uncertainties occur. Bourgon asks herself: “I question how a person who lives surrounded by the crushing beauty of a redwood forest can simultaneously adore it and eliminate it.” Her use of “crushing” triggered me to raise an eyebrow, since her informants may have come up with that word. Later, Bourgon offers a sociologist who credits rural people for their potential the two to really like nature and to reduce trees. We muddled city folk, on the other hand, bemused by trees’ implicit “immortality,” can not summon the essential ambivalence, in accordance to the sociologist.

The trump card in the sawyer’s deck of justifications is played in the book’s concluding paragraph. Hughes absolves himself for his crimes by questioning the pretty possession of the trees. “And if you want to get to the bare bones,” he declares, “all this land belongs to the Yurok” — customers of the area Native American tribe, who until finally this level have manufactured no claims and hardly played a job in the e book at all.

¤

Jeff Wheelwright is the author of The Irritable Heart: The Professional medical Secret of the Gulf War (2001) and The Wandering Gene and the Indian Princess: Race, Faith, and DNA (2012).